Consider Packing These Items When Moving to Italy:

Baby items

Of course, baby items exist in Italy, but they can be significantly more expensive. Not only is it more expensive, sometimes it can be just downright harder to find baby stores and items. The selection is much slimmer. Online shopping, while becoming more of a thing, is not overly present in Italy.

Bring any of your favorite baby items you can’t live without.

A stroller is essential, but think about the sidewalk situation where you’ll be living. Many of the strollers you’ll see in Italy boast the large, all-terrain wheels. Dinky umbrella strollers may be nice for space, but not great on many of the bumpy, sometimes non-existent sidewalks. On the other hand, if you move to a place like where I lived for a bit in Incisa e Figline Valdarno, there were stretches of road with no sidewalks, and the train station had no elevator to get to the train platform. Two large flights of stairs up and down with a stroller isn’t fun. Baby carriers are sometimes preferable. Naples was another city we visited that a baby carrier was invaluable. Too many twisty turns, narrow sidewalks, stairs, and hills to comfortably push a stroller.

Baby Clothes: Some moms prefer to bring over baby clothes because they’re cheaper in the USA, sometimes higher quality, fit better, and overall there is a bigger selection. Knotted baby gowns, bamboo sleepers, etc. are hard to find or not really available in Italy.

Cloth Diapering: I wanted to cloth diaper my son, but I had a difficult time finding cloth diapering products. I could not find any stores that carried cloth diapers. In the end I ordered some pocket cloth diapers from Amazon along with some prefolds and other things. What I didn’t realize was the quality of the prefolds was significantly less than what you would get in the States. I ended up with a lot of leaks, and wasn’t sure why people I knew who had cloth diapered in the States seemed to be having such a different experience than I was all while using the same products.

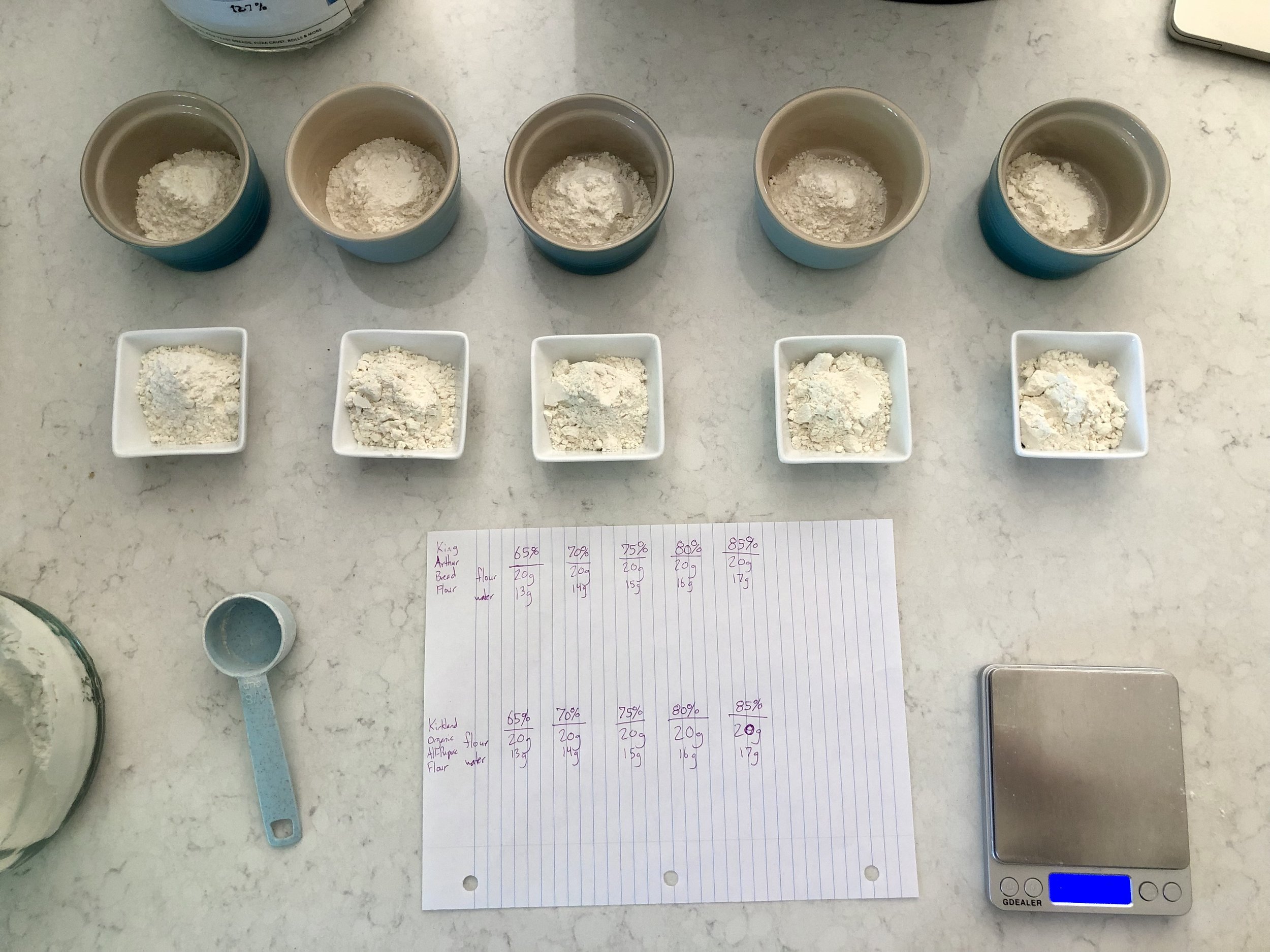

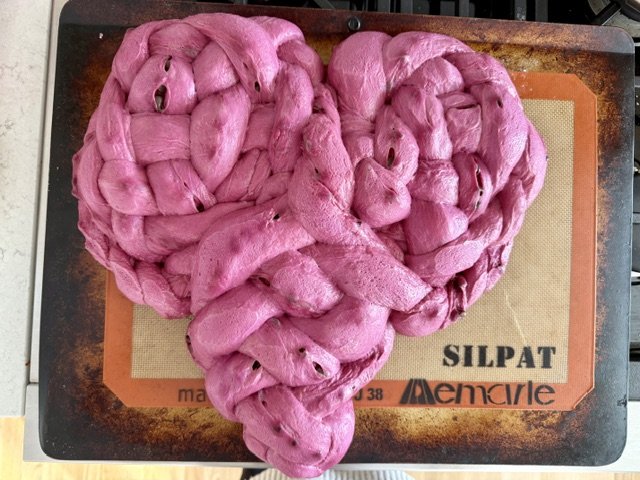

Baking supplies and ingredients

It might seem nonsensical to bring food and baking items to a country famous for its good food. Some ingredients just don’t act the same, or are not available, so if you are wanting to make recipes from your home country, you might need to pack accordingly. Otherwise you’ll be subbing Italian ingredients and it won’t taste like it does back home.

Baking Powder: The Italian baking powder doesn’t act the same as American baking powder. Don’t ask me why, but I am among a number of people who always bring their own baking powder over. It doesn’t take up much room and lasts a long time, so why add one more uphill battle of trying to learn a new baking powder in your favorite recipes if you don’t have to?

Maple Syrup: Maple syrup is available at certain stores, but it is expensive and not as flavorful as the homemade stuff I’m accustomed to. Maple syrup is heavy and a liquid, but if I had extra room, I’d always sneak in a quart or two in my checked luggage. I know others felt the same way, must be an American and Canadian thing. Others found success ordering it online.

Peanut Butter: You will be able to find Peter Pan and Skippy peanut butter here for a hefty price (around 5euro for a small bottle) along with some other brands you’ve probably never heard of, like Calvè (made in the Netherlands), for a bit less, but with each their own unique taste and consistency. If you love and are partial to certain kinds of peanut butter, you might want to bring a few jars of your favorite kind with you.

Vanilla Extract: Italy doesn’t have real vanilla extract, they use either whole vanilla beans or the artificial vanilla flavor “vanillin”. Since vanilla beans are expensive and I didn’t want to use the artificial vanillin they have readily available in grocery stores, I would bring over a large bottle (16oz) with me to use while making and aging my own vanilla extract.

Other food items that can be found in Italy but are different and sometimes more expensive, would include

Brown sugar - can be found, but is usually a different kind of “brown” sugar, and can vary, depending on where its found

Canned pumpkin - can be found for about 4x the price of American canned pumpkin. I would often bring 2 cans if I had extra room to use at Thanksgiving time

Chewing Gum - Italy has chewing gum but their flavors are primarily licorice, not as minty, and flavors don’t last as long

Chocolate chips - Italy only sells mini chips, in white or dark chocolate

Ground Cloves - whole cloves are readily available, but if you don’t have a way to grind them, then bring your own ground cloves. I never once found ground cloves

Marshmallows - different consistency

Pecans - can be found, but often in tiny bags and quite pricy

Pretzels - different consistency

For more things that are difficult to find in Italy (and where to find them, if applicable) check out this post here.

Beauty and Personal Products

You may or may not realize how attached you are to the beauty and personal care products you use until you can’t find them. Italy has some great products, but change is hard. Some find success by gradually trying and changing over products…finding some mascara they like, finding some face lotion they like, finding some deoderant they like. Others use and love a specific product and just aren’t able to find a comparable product in Italy. They bring over enough to last them until the next time they are able to get some.

If using natural products is important to you, an extra challenge is added on having to find all-new, trustworthy and effective natural products in a new language and new stores. The good news is that a lot of the ingredients are the same in Italian as in English. The bad news is that despite what a lot of people in the US think, food and products in Italy are not wholly natural and pure. Yes, they do ban more ingredients than the US as far as I understand, but I was unpleasantly surprised at some of the ingredient lists in Italy. I guess I had imagined waltzing into the Italian stores and picking up any ol’ shampoo or lotion, etc., and not having to worry about checking the ingredients because everything in Europe is natural and wonderful, right? Not exactly.

Books

Books in Italy are, you guessed it, primarily in Italian, but you can find other languages. It might be harder to find them, but they do exist. You can also become a member at a local library where they most likely have foreign language sections.

For specific books you really want to have in English or other languages, I know many people who just bring them with them. Books can get heavy quickly, but you can’t find every book in Italy. After all, books are a one time purchase. I brought over some of my favorite cookbooks and a few reading books I figured I wouldn’t be able to find in Italy.

On the other hand, encourage yourself to read books in Italian. This will help expand your vocabulary and master the language. Italian has a specific tense called narrative tense (for written word), so not always helpful for speaking, but still helpful to learn. I learned a lot by reading. If your level of Italian is still basic, start with children’s books. Seriously. Even baby books I would learn things from. Once you start getting better, move on to books you enjoy and are familiar with in English. At one point I borrowed the Harry Potter series from the children’s section at my local library. It’s very enlightening and empowering to not only be learning, but also understanding and laughing at the humor you know so well, in another language!

Children’s clothing

Similar to the baby clothing mentioned above, I know some moms who prefer to bring over children’s clothes rather than buy them all in Italy. In the US they’re often cheaper, higher quality, and fit better.

Cotton clothing

I’m sorry, is there no cotton in Italy? I remember feeling a bit befuddled the first time I heard of others preferring “US cotton” over Italian made cotton shirts. Apparently, cotton clothing made in the US (or rather sold in the US) is thicker and more durable. Italian cotton is thin.

Once this was brought to my attention I started to notice, by golly, they were right. The cotton is not the same! Cotton clothes I had brought with me were thicker and tended to last longer. Clothing I bought in Italy, especially at some of the smaller boutiques, was very thin and light. I won’t say either one is bad or worse, you can decide that for yourself, but here are some things to consider:

Thicker cotton from the US will last longer

Thinner cotton from Italy stretches out more easily

Thinner cotton is lighter and very nice in the hot, Italian summers

Electronics and their adapters

Electronics can be a tricky thing to pack. Technology isn’t often intended to change countries, outlets, and voltage.

For the electronics you must bring with you, ensure you have the proper adapters and power converters. Check them to see if they might be dual voltage, usually with 120/240V written somewhere near the plug. Smart phones including Apple products are dual voltage, so that’s a good start!

Here are some random things that you would be better off buying in Italy:

Printer

Hair dryer, straightener, curler, etc.

Electric mixer, any electric kitchen gadget - I desperately wanted to bring my Kitchen Aid stand mixer. Kitchen Aid’s aren’t cheap in the US, and they’re more expensive in Italy than the US. But with the weight of a Kitchen Aid and the risk of burning the motor even with a fancy power converter, it just wasn’t a good idea. I had read of people ruining their Kitchen Aids trying to run them on power converters and adapters.

A printer story: I somehow inherited a printer from a friend who moved back to the USA. The printer was from the US, and I’m really not sure why someone brought a printer over when they should’ve bought one in Italy. As it turns out, it came in handy with all of the documents and copies that need to be made with life in Italy. It didn’t require a power converter, just an adapter. The problems started when I needed to change the ink cartridges. The grocery stores didn’t carry the cartridge numbers the printer needed. I quickly found out that the printer was in US mode, and had to be reconfigured to European mode. Once reconfigured to European mode, I could buy the Italian cartridges and start using it again. As would happen to me, it took literally hours on the phone with several different people from HP trying to change the printer’s country setting, then trying to troubleshoot why it would not. It turned out the printer could not be changed, and HP sent me a whole new printer AND ink cartridges. Seriously, while Italian customer service averages on “average” at best, sometimes downright awful, HP was this shining beacon of “we’ll do anything to make this right” and not somehow always making it the customer’s fault. They even sent me a box and scheduled UPS to pick up and recycle the old printer so I didn’t have to. Why the long story? This is your warning to do your research before just bringing electronics to a different country.

On the bright side, I was able to bring an essential oil diffuser with me because it was dual voltage!

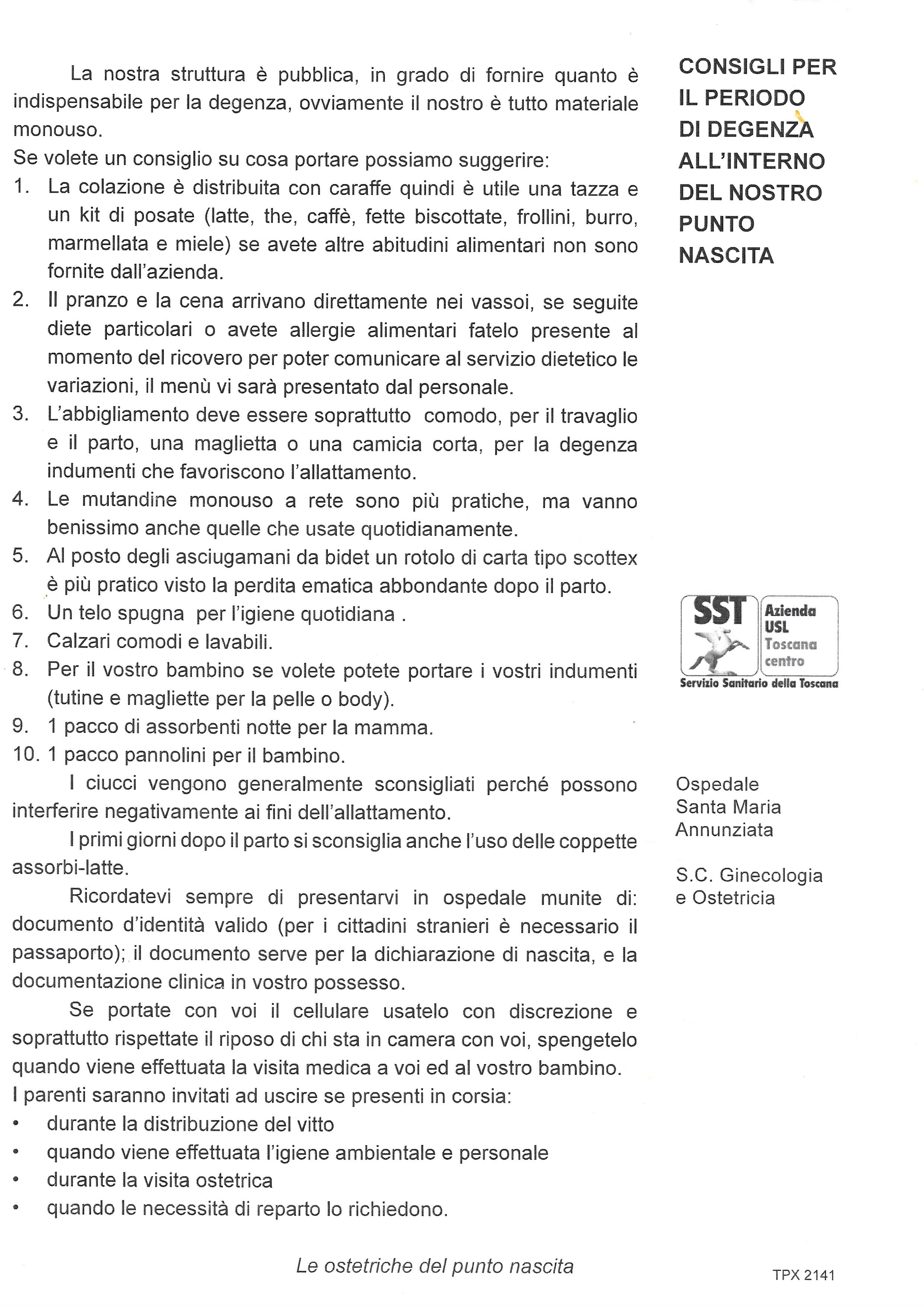

Important documents

While you might not think you’ll need certain important documents in Italy, you can make your life a lot easier by scanning important documents onto your computer and bringing copies with you. Paper does not take up much space and you would be surprised what you might need while you’re there, or even for taking care of business back home.

Some ideas of what to bring, scan or bring copies of:

Medicinal Items

Over the counter medication is cheaper in the States than in Italy, among other medicinal items. Also, not all medications that are OTC in the States are OTC in Italy. You usually need a script for ibuprofen (in Italian “brufen” or “Nurofen”) and even acetaminophen or paracetamol (American brand name Tylenol, Tachipirina in Italian) requires a prescription for the 1000mg caplets.

You might also want to consider bringing any allergy medications and important prescription medications until you can figure out if/where you can get those in Italy.

I also know of a few people who specifically bring Neosporin with them.

Mosquito spray is another item I’ve heard people like to bring with them, especially if there is a favorite brand or kind. Italy does have mosquito spray, but I haven’t tried it to tell you how it works. I can tell you the mosquitos can be pesky and miserable in the summer. Italy does have these wall plug-ins that last 1-2 months and can be turned off and on as desired, that work excellently at keeping mosquitos at bay. They can be invaluable for those who suffer mosquitos, but I use them with caution because I’m not entirely sure what fumes they’re letting out. I avoid using them around kids where possible.

Sentimental Items

Bring anything of sentimental value that can’t be purchased in Italy. Space in suitcases and packing containers might be limited, but I always liked having a few key items from home. Jewekry, decor, children’s artwork, picture frames, etc, might be a wonderful source of comfort while away.

If you have children who have favorite stuffies or toys, consider bringing a duplicate for if/when the favorite item gets lost or worn out.